Working Diagnosis:

Subdural Hematoma

Treatment:

The athlete was taken to the operating room, 72 minutes after hospital arrival and underwent a left frontotemporal parietal decompressive craniectomy with evacuation of subdural hematoma. Following surgery, pupils were 2 mm bilaterally and a repeat CT showed good midline resolution. Case Photo #2 The intracranial monitoring showed improved pressures.

Outcome:

Hospital complications included pneumonia, wound infections, hydrocephalus and seroma formation. The patient was discharged after 18 days to home with outpatient speech, occupational, and physical therapy.

The athlete was able to return to school one month after injury. In the interim, he had removal of his ventriculoperitoneal shunt, a cranioplasty and graduated from high school. He is no longer participating in organized or contact sports.

The patient continues to have issues with executive functions, exertional/positional headaches, and impulsive behaviors. He has been discharged from all therapy services.

Author's Comments:

The case presented above represents a patient with rapid deterioration related to acute subdural hematoma, a rare but serious brain injury in high school football. Given the potentially serious outcomes related to this injury, including death, rapid and appropriate treatment are imperative. Here, we discuss multiple factors which contributed to his survival despite the severity of his initial presentation.

Appropriate Suspicion:

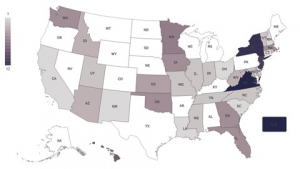

In addition to our case report, multiple prior reports of subdural hematoma in football players exist (3,5-7,9,11-13). These cases highlight the ways in which acute subdural hematoma can present. Reported initial symptoms include headache, vertigo, nausea and emesis, which can rapidly progress to seizure, loss of consciousness, and unequal pupils. There is often clear provoking physical contact within the game although, as with our case, a clear inciting play is not always identified (5,6,7,9,13). In most reported cases, there is a chronologic association with recent symptoms from separate incidents of physical contact. This can range from earlier in the same game to weeks prior (3,5,9,11-13).

It should also be noted that our player had a history of multiple concussions. The most recent concussion had been more than a year prior to suffering a subdural hematoma. However, in other cases subdural hematoma occurred within weeks of returning to play (3,9,11,13). Our case may suggest that this risk persists for a longer duration post-concussion.

Sideline Evaluation:

For anyone sustaining a subdural hematoma of similar severity to this case, a proper response from the sideline medical professionals is vital. The first step in sideline management for an unconscious patient is assessing the ABCDEs. Particular attention should be given to head and cervical spine injuries. Guidelines exist for assessing and managing cardiac arrest and concussion, however, there are no published guidelines to address severe brain injury or bleed. While a patient is being stabilized, an ambulance should be summoned for rapid transfer to an emergency department. Rapid emergency activation is imperative and enables an expedited transfer to an appropriate trauma center given the risk of rapid deterioration. In the case, the patient was quickly transferred to a higher level of care.

Rapid Medical Intervention:

Efficient management is an important factor contributing to outcome. It took approximately 45 minutes from the time symptoms first presented to arrival at the emergency department. During this time, the on-field physician was in communication with the emergency department, allowing for activation of the neurosurgical team and preparation for the patient's arrival. This allowed for planning a rapid CT scan to confirm the diagnosis and transferring of the patient to the operating room for surgical decompression within 72 minutes.

Indications for surgical intervention include a clot thickness greater than 10 mm or midline shift greater than 5 mm regardless of GCS score. In addition, patients with a GCS drop of at least 2 points from the time of injury to hospital admission and/or presents with asymmetric or fixed and dilated pupils. Surgery is also recommended if intracranial pressure monitoring (ICP) is consistently greater than 20 mm Hg in a comatose patient (GCS <9). In the case of our patient, both his midline shift and asymmetric pupils indicated surgical intervention. Performing evacuation within 2-4 hours of clinical deterioration has been shown to lead to better outcomes. Some studies suggest outcomes to be superior when surgical intervention happens within 2 hours.

This highlights the importance of rapid intervention. Because of the timely sideline intervention and coordination while en route to the hospital, he was into the operating room approximately two hours after initial symptoms. Albeit, this patient has some executive functioning impairments, exertional/positional headaches, and impulsivity behaviors, it is likely he would have more severe impairments, and may have died, had intervention not been prompt.

Editor's Comments:

A subdural hematoma is one of the leading causes of head injury death. A subdural hematoma may occur after a single or multiple traumatic blows to the head. In one case study, a football player who has received a minor head injury was noted to be 4 times as likely to sustain a subsequent head injury. Subdural hematomas result from the tearing of the bridging veins leading to swelling and herniation of brain tissue which may cause ischemia and death. Thus, these occurrences are potentially life threatening and must be recognized and managed promptly to prevent a catastrophic outcome. Major injuries involving the central nervous system are rare neurologic emergencies that require early intervention and appropriate triage to the appropriate level of care.

References:

1. Bullock MR, Chesnut R, Ghajar J, et al. Surgical management of acute subdural hematomas. Neurosurgery. 2006;58(3 Suppl):S16-24; discussion Si-iv.

2. Haselsberger K, Pucher R, Auer LM. Prognosis after acute subdural or epidural haemorrhage. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1988;90(3-4):111-116.

3. Kersey RD. Acute subdural hematoma after a reported mild concussion: a case report. J Athl Train. 1998;33(3):264-268.

4. Kramer EB, Serratosa L, Drezner J, Dvorak J. Sudden cardiac arrest on the football field of play--highlights for sports medicine from the European Resuscitation Council 2015 Consensus Guidelines. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(2):81-83.

5. Litt DW. Acute subdural hematoma in a high school football player. J Athl Train. 1995;30(1):69-71.

6. Logan SM, Bell GW, Leonard JC. Acute Subdural Hematoma in a High School Football Player After 2 Unreported Episodes of Head Trauma: A Case Report. J Athl Train. 2001;36(4):433-436.

7. Matsuda W, Sugimoto K, Sato N, et al. Delayed onset of posttraumatic acute subdural hematoma after mild head injury with normal computed tomography: a case report and brief review. J Trauma. 2008;65(2):461-463.

9. Okonkwo DO, Tempel ZJ, Maroon J. Sideline assessment tools for the evaluation of concussion in athletes: a review. Neurosurgery. 2014;75 Suppl 4:S82-95.

10. Potts MA, Stewart EW, Griesser MJ, et al. Exceptional neurologic recovery in a teenage football player after second impact syndrome with a thin subdural hematoma. Pm r. 2012;4(7):530-532.

11. Shah S, Luftman JP, Vigil DV. Football: sideline management of injuries. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2004;3(3):146-153.

12. Shell D, Carico GA, Patton RM. Can Subdural Hematoma Result From Repeated Minor Head Injury? Phys Sportsmed. 1993;21(4):74-84.

13. Treister DS, Kingston SE, Zada G, et al. Concurrent intracranial and spinal subdural hematoma in a teenage athlete: a case report of this rare entity. Case Rep Radiol. 2014;2014:143408.

14. Yengo-Kahn AM, Gardner RM, Kuhn AW, et al. Sport-Related Structural Brain Injury: 3 Cases of Subdural Hemorrhage in American High School Football. World Neurosurg. 2017;106:1055.e1055-1055.e1011.

Return To The Case Studies List.