|

- Home

-

About Us

-

- FAMSSM Applications

-

Application submission is now open for the 2025 Class of AMSSM Fellows. New Fellows will be announced to the AMSSM membership after the first of the year and honored at the 2025 Annual Meeting.

Applications for the FAMSSM Designation will be available on an annual basis. Please contact Ellen Glasgow with any questions regarding the FAMSSM application.

-

- We Understand You

-

Membership

-

- AMSSM Trainee Case Competition

Event -

Fellow, Resident, and Student Members (Limited Registration). To register, Click here. Under the Membership heading, scroll down to the Event Link to register for a spot on a team. Your team will be given a sports medicine case to present at the event.

- AMSSM Trainee Case Competition

-

Communications

-

- Online AMSSM Community for Members

-

AMSSM Collaborate online community provides a forum for year-long connection, giving members the chance to have conversations, share resources and make connections with your peers.

-

Education

-

- Education

- Conferences

- Abstract Submission

- Case Studies

- US Case Studies

- MSK Radiology Series

- AMSSM YouTube Channel

- Podcasts

- Free ECG Training Module

- Biologic Association

- Online Learning/CME

- Virtual Exam Toolkit

- Testing Center & Review

- Test Score Access

- Sports Medicine Curriculum

- Fellowship

- Fellow Online Lecture Series

- Residency

- Medical Student

- Educational Content for Members

-

- AMSSM Fellow Online Lecture Series

-

The AMSSM National Fellow Online Lecture Series features talks from national experts on fundamental sports medicine topics pertinent to fellowship training and sports medicine board certification. Go to the collaborate.amssm.org site and view the available lectures in the Upcoming Events area.

-

- Research

-

Advocacy

-

- Advocacy

- Advocacy

- AMSSM Choosing Wisely Recommendations

- AMSSM Sports Medicine Physician Scope of Practice

- Issue Briefs

- State Legislative Contact Resources

- Legislators / Insurers Resources

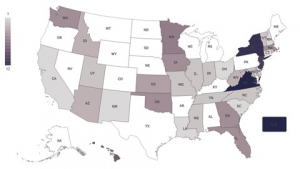

- Legislation By State

- Advocacy Resources

- Principles that Determine AMSSM's Support for Policy and Legislation

- Sports Medicine Practice Questions

- High School Team Physician Tool Kit

-

-

Sports US

-

Patients

-

- Need a Sports Medicine Physician?

-

FindADoc

-

Additional Information

-

- Additional Information

- Sports Med Today

- Journals

- Weekly Digests

- Store

- Careers

- Industry

-

-

-

-

Foundation

-

- Foundation

- Foundation

- About Us

- History and Mission

- Foundation Board

- Awards

- Member Support

- Member Contributors

- Member Contribution

- Industry Support

- Sponsorship Opportunities

- Sponsorship

- Make a Gift

- Donate to Auction

- Contact Us

- Education

- AMSSM International Traveling Fellowship Program

- AMSSM Global Exchange Fellowship

- Fellow Starter Kits

- Free ECG Training Module

- Scholarships

- All Foundation Sponsored Research Grants/Awards

- Humanitarian

- Humanitarian Service

- Medical Disaster Relief

- AMSSM Annual Meeting Service Project

- AMSSM Local/Global Service Projects

-

-

-